Coppicing, pollarding and shredding

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Coppicing, pollarding and shredding all tend to result in shorter harvest cycles than many other standard forestry products. The techniques all differ slightly but essentially involve harvesting timber from a tree without disturbing the roots of the tree or the soil. This can limit the size of the possible timbers that can be harvested but removes the need for replanting and it has been shown it can also have reduced environmental impacts from both an ecological and emissions perspectives.

Although trees contain sequestered carbon within their stem and crown, a considerable amount of carbon is also stored within the root system and in the soil surrounding the roots. When roots are disturbed some of this carbon can be released. Coppicing and pollarding, because they leave roots untouched, can have reduced impacts.

Traditionally the harvested wood has been used for fence posts, craft projects as well as small structures. In recent years with improved finger jointing technology short lengths of coppice wood can produce longer knott free boards. UK manufactured products include external cladding boards, glue-laminated beams, carpentry material and flooring, as well as complete buildings such as timber gridshells.

[edit] Coppice types

There are a number of different methods of coppicing, which are described below.

[edit] Simple coppicing

Simple coppicing is when a woodland is managed with similar aged trees each with the stems cut at around head height, to produce small/medium-sized round wood for poles. Depending the size of timbers needed, the species, location, rate of growth, environmental and social requirements, the trees can be cut on a regular rotation. The forest might be divided into areas that have the same harvest rotation cycle, normally anything between 15 and 30 years, with these grouping of trees called coupes. This type of coppice management is called an in-cycle or in rotation coppice woodland.

[edit] Coppicing with standards

Coppice with standards is managed with differing heights of trees. In general some will be cut very low down ( called an underwood) and some very high, this gives a variety in the size of timber products that can be harvested. This approach can be more difficult to manage than simple coppicing because the species, number, age and location of taller trees needs to be balanced with their effect on the growth of the smaller trees or underwood. Which trees are left to grow and which are cut changes with time and balanced with preventing too much overshadowing and new tree growth.

[edit] Selective coppicing

In selection coppice, 2 or 3 cycles are used to harvest trees at the stem of differing sizes, there maybe 3 different rotations made on the same coppice stool, this provides repetition of specific size or shape products for different uses. Examples of this approach might be found in the furniture beechwood and holm oak coppice as well as hazel grown for thin straight rods that are used as thatching spars or slightly longer for fence poles.

[edit] Short rotation coppice SRC

Although coppicing is generally considered a forest trade, short rotation coppice creates thinner stems that allow them to be harvested more similarly to agriculture by hand or machine. Willow (salix spp.) can be grown in short cycles of 2, 4 or 5 years, agriculturally harvested by cutting it at its base to give tall straight 4-metre rods of willow. This has been investigated in the UK primarily as a source of a sustainable fuel because of its short harvest cycle, as a hardy crop that can last some 30 years before requiring replanting. Traditionally it has been used in craft industries to make woven items such as baskets and light structures, some research has also looked at its potential use in the manufacture of board and formed composites. It can also be pollarded and coppiced normally. Poplar (Populus spp.) is best grown in cycles of 4-5 years, producing taller 8-metre lengths but fewer in number. Initial plantings are from cuttings that contain buds. Once established this forms a deep string network of roots which can be difficult to remove. It has a lower bark to wood ratio and is also promoted as a biomass crop in the UK.

[edit] Coppice species

There is some overlap between the types of species that can be coppiced and those that can be pollarded, with some of the main varieties suitable for both.

[edit] Willow coppice

Willows (Salix) are a popular UK species for both pollarding and coppicing because they are hardy and grow rapidly, they might be pollarded every 5-7 years or coppiced over slightly longer periods. Willow wood (Salix Alba ‘Caerulea’) is famous for its use in cricket bats, as it is robust and lightweight, it may also be used in furniture. It is also popular in short cycle (SRC) producing malleable strands for baskets (such as the traditional Sussex Trug), matts or light fences or structures.

[edit] Beech coppice

Beech trees (Fagus sylvatica and grandifolia) can be pollarded or coppiced, the wood being used in the manufacture of furniture as well as flooring, veneers, boatbuilding, cabinets, plywoods and musical instruments. Beech is a hard and strong wood but cannot withstand moisture, so it is not durable externally and is mostly used for interiors. In the UK, traditionally the bodgers of the Chilterns pollarded greenwood beech, using the craft of wood turning on site to form slim furniture legs which were then sold to the local furniture manufacturers.

[edit] Sweet Chestnut coppice

Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) is a popular coppice and pollard species in the south of England, which it is thought was introduced by the Romans. It contains high levels of tannic acid making it a strong durable hardwood, which also produces edible nuts. Traditionally these forests were regularly managed, with some larger oaks that could be harvested on longer rotations. Many of these forests are now over mature (overstood), no longer actively managed and used mainly for recreation. However, because of the strength and durability of sweet chestnut as a modern building material, as well as the environmental benefits, there has been a resurgence of coppicing this timber, using modern finger jointing techniques to produce long regular external timber cladding boards at scale.

[edit] Oak coppice

Oak trees (Quercus) have a great many uses, as the wood with its high levels of tannic acid is very durable. It may also be applicable to pollarding, though in most cases it is a standard forestry product with harvest cycles well over 10 years, and so not considered rapidly renewable. However it can be pollarded and coppiced as a way to harvest smaller parts on shorter cycles for fence posts, railroad ties or floors as well as elements of furniture and interiors. Longer harvest cycles of well over 10 years produce larger timbers which have been used for many years green (not dried), for traditional oak frame structures, using joints and pegs, sometimes called traditional green oak framed buildings.

[edit] Poplar coppice

Poplar (Populus spp.) is best grown in cycles of 4-5 years, producing taller 8-metre lengths but fewer in number. Initial plantings are from cuttings that contain buds. Once established it forms a deep string network of roots which can be difficult to remove. It has a lower bark to wood ratio and is also promoted as a biomass crop in the UK.

[edit] Other species

Other species known to be used in coppicing include Ash (Fraxinus), Alder, Black Locust, Elm (Ulmus), Redbud (Cercis), Sycamore (Platanus) and Tulip tree (Liriodendron).

[edit] Bamboo coppice

Within the Bamboo (Bambusoideae) family there are some 116 genera and over 1400 different documented species that grow all over the world, many of which are suitable for construction and use in furniture. Bamboo is the fastest-growing plant on earth and can be large enough to be used structurally. Some plants can grow at a rate of 0.00003 km/h and the Chinese moso bamboo can grow almost a metre in a single day. Although one might not associate bamboo directly with the traditions of coppicing or pollarding, it is managed in a very similar way either by cutting at the base to produce long poles or topped for smaller products.

Bamboo shoots are connected to their parent plant by an underground stem, called a rhizome, so the shoot doesn’t need leaves of its own, until it reaches full height. Unlike timber, bamboo does not grow in rings that thicken the stalk of a tree, so it is in some ways more efficient, growing straight up as a single stick, meaning it can produce perfectly round quite thick diameters in very straight sections. Some examples of bamboo used in construction are listed but there are many more;

- Common bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris)

- Giant stripy bamboo (Gigantochloa verticillata)

- Giant thorny bamboo (Bambusa bambos)

- Giant timber bamboo (Bambusa oldhamii)

- Golden bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea)

- Balcooa bamboo (Bambusa balcooa

- Big jute bamboo (Dendrocalamus latiflorus)

It has a traditionally been used in construction for centuries and is still used to create construction scaffold towers for buildings. Today is is also processed to make board, flooring and cabinet making materials. It is a durable, hard wearing material that is increasingly being used as a replacement for slower growing timber products.

[edit] Pollarding

Pollarding is a forestry method similar to pruning where the upper branches of a tree are cut back but the base and roots are left intact. It has been a common practice in the UK since medieval times and allowed easy removal of timber for fuel whilst encouraging greater foliage regrowth, which was used as animal feed and bedding.

Pollarded trees often lived longer, and produced denser wood as they grew more slowly. Pollarded forests when maintained may also have had a greater diversity of species because sunlight reaches deeper into the forest as higher branches are cut, along with the greater foliage. It is not however possible to pollard a tree that is already mature, hence many forests where pollarding was carried are now no longer viable for pollard forestry.

Today pollarding is commonly practiced in urban environments, to prevent root invasion and control the overall size of a tree, this needs to be carried out at the right time and then repeated every few years to maintain both the look and size. It is also often carried out on fruit trees, although this may be considered more in line with pruning. In general pollarding can result in quite straight timber growths and therefore products such as fence posts and furniture legs were to be found from pollarded timber. The harvesting cycles of pollards can range anywhere between 1 to 15 years, cutting may have been quite informal with each branch and tree treated according to its own readiness, use and need. However today unless timber sources are known to be pollarded they are most likely not considered rapidly renewable.

[edit] Pollard species

In general most species that can be coppiced can also be pollarded, however Sweet Chestnut, Willow and Beech were commonly pollarded. Other species known to be suitable for pollard management are Maples (Acer), Black locust or false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia), Hornbeams (Carpinus), Lindens and limes (Tilia) aswell as Planes (Platanus), Horse chestnuts (Aesculus), Mulberries (Morus), Eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) Yews (Taxus) and even Moringa trees.

[edit] Shredding

Shredding is the practice of cutting side branches from the main trunk of a tree while retaining the crown, typically to provide wood and fodder for livestock. Unlike pollarding, the tree is not decapitated and continues to grow upwards as a single stem tree, ultimately able to provide large dimension timber. Shredded trees are typically found alongside tracks or field boundaries and also in some pasture-woodland systems.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

- Bodgers.

- Chain of custody.

- Confederation of Timber Industries.

- Deforestation.

- European Union Timber Regulation.

- Forests.

- Forest ownership.

- Forest Stewardship Council.

- Legal and sustainable timber.

- Legally harvested and traded timber.

- Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification.

- Sustainable timber.

- Timber.

Featured articles and news

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

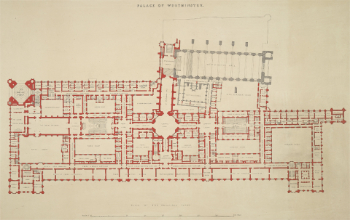

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.